Understanding the relationship between letters and sounds, and how to use this knowledge to decode (read) and encode (spell) words. Phonics instruction enables students to sound out words, making reading and spelling more automatic over time.

Phonics helps beginning readers “crack the code” of written language. When children learn how letters match sounds, they can start reading words and writing them too. On this page you will learn what effective phonics instruction looks like and why it’s such an important part of learning to read. Teachers and families can support children by making phonics practice clear, engaging, and systematic.

Overview

Mini Mastery- Phonics

What is Phonics?

Phonics is understanding the relationship between letters and sounds, and how to use this knowledge to decode (read) and encode (spell) words. Phonics instruction enables students to sound out words, making reading and spelling more automatic over time. When children know the letter B says /b/ and t-i-o-n says /shun/, they’re using phonics.

The ability to apply these predictable relationships to familiar and unfamiliar words is crucial to reading success.

Phonics is not a specific reading program. However, it is an important part of explicit and systematic instruction for beginning readers.

What does Phonics instruction look like?

Systematic phonics instruction begins with teaching basic letter-sound correspondence, which is the relationship of the letters in the alphabet to the sounds they represent. Over time, it progresses to teaching more complex letter-sound relationships so that students can decode regular and irregular words.

Phonics instruction should be targeted to the specific needs of the student or class. It should be evidence-based, engaging, systematic, and explicit.

So, how do we teach Phonics?

While there isn’t a specific, agreed upon instructional sequence for introducing letter-sound relationships, it’s important to begin with the sounds that will enable students to begin reading words as quickly as possible.

Start with letter-sounds of high utility such as /m/, /a/, and /s/ so students can begin working with words as soon as possible. Work with just a few sounds at a time by teaching each letter of the alphabet and its most common corresponding sound. Instruction should include naming the letter or letters that represent the sound.

Separate and stagger letter-sound relationships that are auditorily confusing (b and v) or visually similar (b and d) to promote mastery of one before introducing the other that may create confusion.

When introducing each letter-sound relationship in isolation (versus when reading connected text), associate a word beginning with that letter-sound and follow up by introducing an object or picture of that word. Visually representing a word containing the letter-sound being taught can help a student remember the relationship between the letter and the sound.

Use that word to create a short sentence or story, read the sentence aloud and then introduce the object or picture. By reinforcing the letter-sound with both the letter in print and the object, this helps the student recall the sound when they encounter the letter later.

It’s important to note that pictures as part of phonics instruction are used to associate the sound to the letter and help with memory of that letter and it's sound. The pictures are not used to predict or decode words.

Letters should be introduced in uppercase and lowercase when teaching the relationships between letters and sounds.

Provide multiple opportunities for students to practice with letter-sound relationships.

Once students have a good grasp of the letter-sound relationship you are targeting and are moving on to connected text, focus solely on the letters and sounds in the words. Pictures are not part of the continued building of phonics skills.

Finally, why is Phonics important?

Phonics helps crack the code of written language. Knowing the sounds of letters will help children decode words, which eventually leads to reading.

This skill also helps children know which letters to use when writing – encoding.

It’s important to note that phonics is what connects instruction in phonemic awareness – The ability to recognize and manipulate individual sounds in spoken words – to actual print. Phonics has a profound impact on fluency – the ability to read text accurately, quickly, and with proper expression, and reading comprehension – the ability to understand, interpret, and gain meaning from written text.

Correctly and quickly decoding, or sounding out words, allows children to focus their attention and energy on understanding what they read, which is what we want all children to be able to do.

Download Infographic

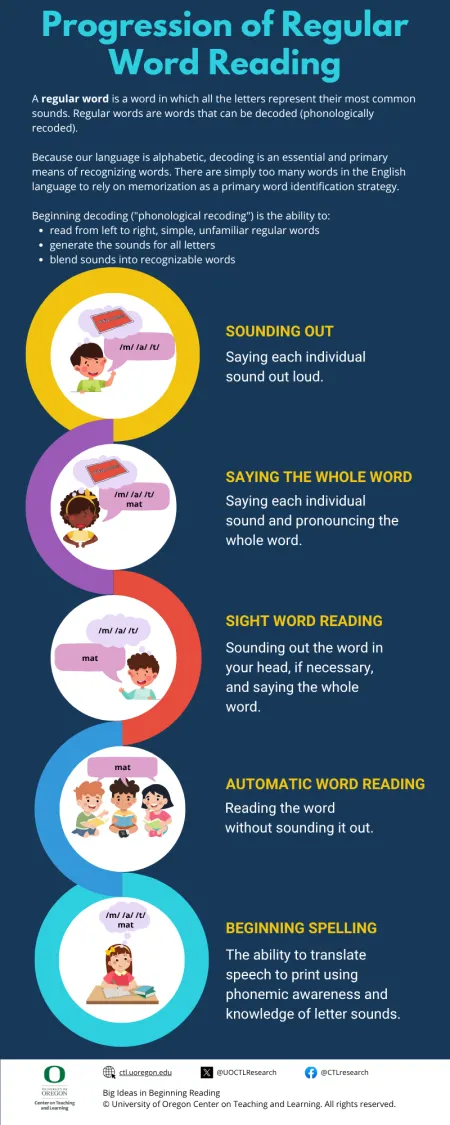

Progression of Regular Word Reading

A regular word is a word in which all the letters represent their most common sounds. Regular words are words that can be decoded (phonologically recoded).

Because our language is alphabetic, decoding is an essential and primary means of recognizing words. There are simply too many words in the English language to rely on memorization as a primary word identification strategy. Beginning decoding ("phonological recoding") is the ability to:

- read from left to right, simple, unfamiliar regular words

- generate the sounds for all letters

- blend sounds into recognizable words

Sounding Out

Saying each individual sound out loud.

Saying the Whole Word

Saying each individual sound and pronouncing the whole word.

Sight Word

Reading Sounding out the word in your head, if necessary, and saying the whole word.

Automatic Word Reading

Reading the word without sounding it out.

Beginning Spelling

The ability to translate speech to print using phonemic awareness and knowledge of letter sounds.

Download Infographic

Role of Reading

The role of phonics instruction is to help students understand and apply the alphabetic principle—the concept that letters and letter combinations represent the sounds of spoken language. This knowledge allows students to decode unfamiliar words and supports accurate, fluent reading.

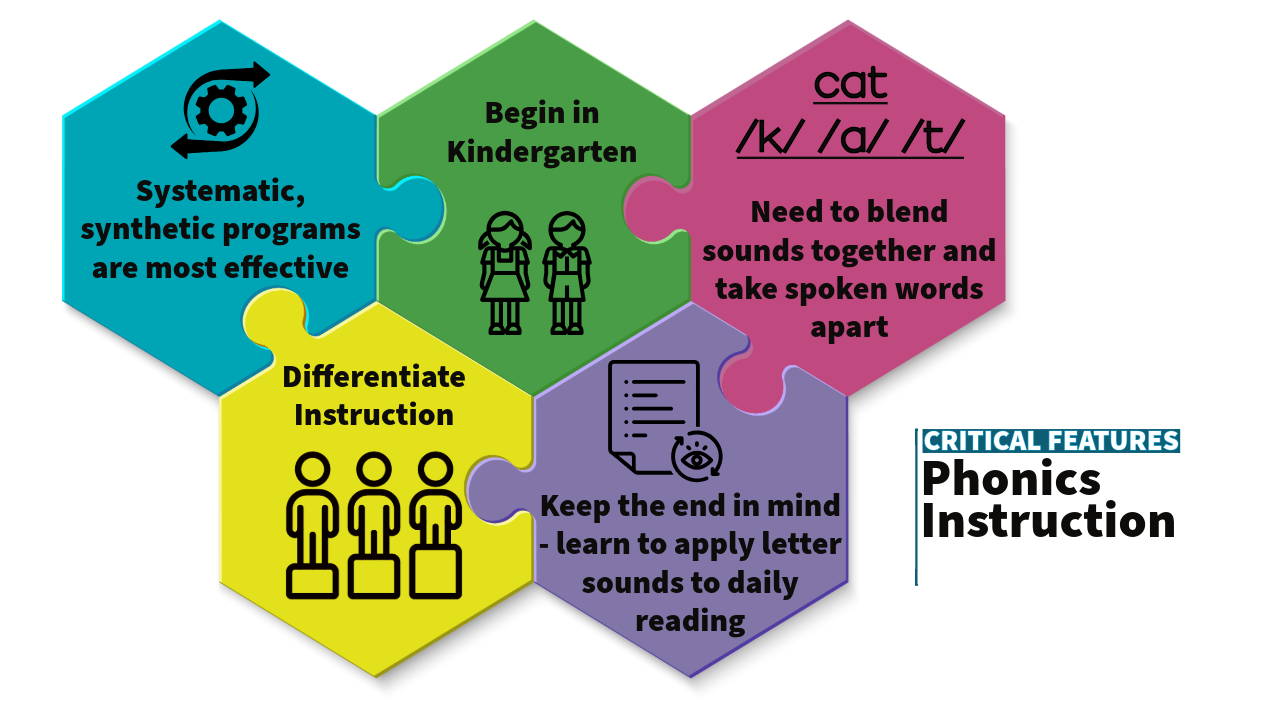

Effective phonics programs are systematic, start early in kindergarten, connect to phonemic awareness, and are differentiated to meet student needs, always keeping the ultimate goal of applying these skills to actual reading and writing in mind.

Critical Features of Phonics Instruction

Effective phonics instruction is:

Systematic and synthetic. The most effective programs follow a carefully sequenced progression and explicitly teach how to blend individual letter sounds into words.

Introduced in kindergarten. Instruction should begin early, focusing on simple letter-sound correspondences and building a foundation for decoding.

Tied to phonemic awareness. Students must learn to blend sounds to form words and segment spoken words into individual sounds to make sense of how print maps onto speech.

Differentiated to meet student needs. Instruction should be adjusted based on student performance, ensuring all learners receive targeted support.

Focused on the goal of reading. The ultimate aim is for students to apply their phonics skills to real reading and writing tasks, connecting sound-symbol knowledge to meaningful text.

Assessment in Action

Nonsense Word Fluency Scoring

Watch this video to see a demonstration of how to score nonsense word fluency. For more information, see the DIBELS Research Site

.

The Science of Reading

Research shows that explicit, systematic phonics instruction significantly improves early reading outcomes. Students who develop strong phonics skills can decode unfamiliar words more easily, which leads to better fluency and comprehension. Phonics instruction helps children move from sounding out words to reading with understanding and ease.

Key Citations and Research

- Carnine, D., Silbert, J., & Kame’enui, E. J. (1997). Direct instruction reading. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

- Ehri, L. C. (1991). Development of the ability to read words. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 2), 383–417. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Harn, B., Simmons, D. C., & Kame’enui, E. J. (2003). Institute on Beginning Reading II: Enhancing alphabetic principle instruction in core reading instruction [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://slideplayer.com/slide/4959318/

- Liberman, I. Y., & Liberman, A. M. (1990). Whole language vs. code emphasis: Underlying assumptions and their implications for reading instruction. Annals of Dyslexia, 40(1), 51–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02648140

- National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (No. 00-4769). Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Retrieved from http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/nrp/smallbook.htm

- Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360–407. https://doi.org/10.1598/rrq.21.4.1

- Wagner, R. K., & Torgesen, J. K. (1987). The nature of phonological processing and its causal role in the acquisition of reading skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.192

- Ehri, L.C. (2020). The Science of Learning to Read Words: A Case for Systematic Phonics Instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.334